Storyboarding

Storyboarding Your Film

By making a storyboard (instead of improvising your way through) you get a high degree of control. This ensures that the project is realistic within the given time.

By using a storyboard you reduce the risk of lacking important shots in the editing room. It is clear, however, that the storyboard of a documentary cannot be as accurate as that of a fiction film (which does not mean that it shouldn't be as detailed as possible): You cannot plan the exact length of the different shots, at least not those involving 'real-life' people. Try not to be too ambitious when it comes to the number of stories that you want people to tell. Telling a story often takes longer than you expect.

One of the fascinating aspects about filming reality is that it cannot be controlled. Invariably, new possibilities will turn up along the way. Thus, the storyboard should always be regarded as a preliminary script that can be adjusted on location. Just remember that the danger of improvising a lot is that you might end up with a story lacking some of the essential elements.

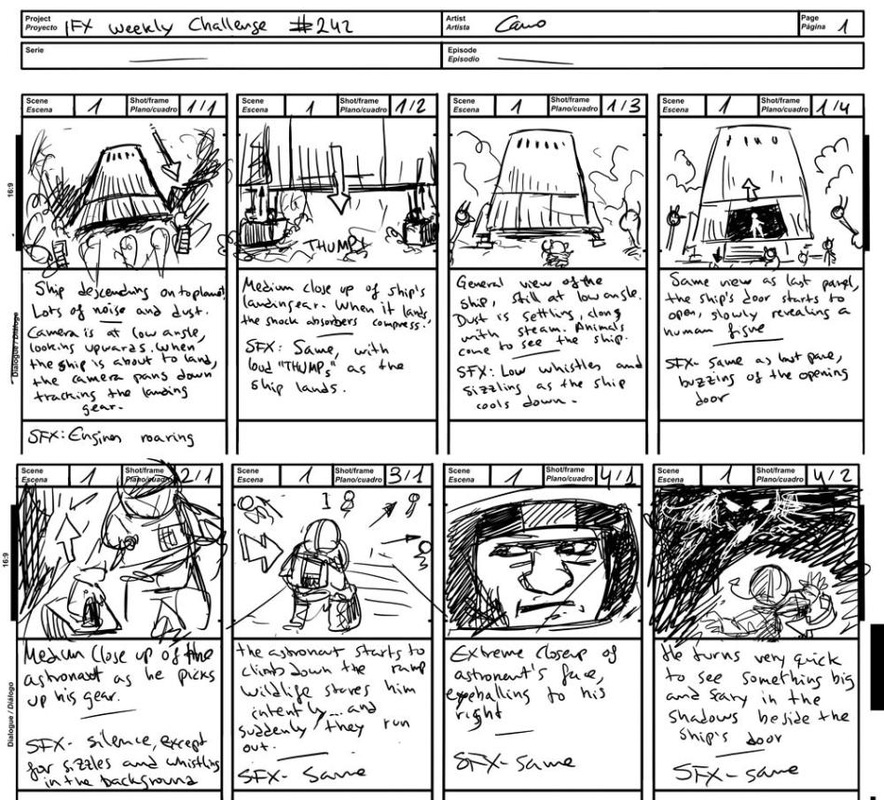

Before you create your film storyboards, you have to perform certain tasks and make certain decisions. First, begin by evaluating your screenplay and picturing it in terms of separate shots that can be visually translated into individual storyboard panels. Then you determine what makes up each shot and also which images need to be storyboarded and which ones don't. After you start storyboarding, you'll need to determine whether you're shooting for a TV movie or a theatrical release, which will ultimately affect the frame dimensions of your panels.

By making a storyboard (instead of improvising your way through) you get a high degree of control. This ensures that the project is realistic within the given time.

By using a storyboard you reduce the risk of lacking important shots in the editing room. It is clear, however, that the storyboard of a documentary cannot be as accurate as that of a fiction film (which does not mean that it shouldn't be as detailed as possible): You cannot plan the exact length of the different shots, at least not those involving 'real-life' people. Try not to be too ambitious when it comes to the number of stories that you want people to tell. Telling a story often takes longer than you expect.

One of the fascinating aspects about filming reality is that it cannot be controlled. Invariably, new possibilities will turn up along the way. Thus, the storyboard should always be regarded as a preliminary script that can be adjusted on location. Just remember that the danger of improvising a lot is that you might end up with a story lacking some of the essential elements.

Before you create your film storyboards, you have to perform certain tasks and make certain decisions. First, begin by evaluating your screenplay and picturing it in terms of separate shots that can be visually translated into individual storyboard panels. Then you determine what makes up each shot and also which images need to be storyboarded and which ones don't. After you start storyboarding, you'll need to determine whether you're shooting for a TV movie or a theatrical release, which will ultimately affect the frame dimensions of your panels.

Breaking down your script

The task of turning your screenplay into a film can be very overwhelming. But remember, a long journey begins with a single step, so begin by breaking the screenplay down into small steps, or shots. A shot is defined from the time the camera turns on to cover the action to the time it's turned off; in other words, continuous footage with no cuts. Figure out what you want these shots to entail and then transform those ideas into a series of storyboard panels. Stepping back and seeing your film in individual panels makes the project much less overwhelming.

Evaluating each shot

You have several elements to consider when preparing your storyboards. You first need to evaluate your script and break it down into shots. Then, as you plan each shot panel, ask yourself the following questions:

- What is the location setting?

- How many actors are needed in the shot?

- Do you need any important props or vehicles in the shot?

- What type of shot (close-up, wide-shot, establishing shot, and so on) do you need?

- What is the shot's angle (where the camera is shooting from)? Is it a high angle? A low angle?

- Do any actors or vehicles need to move within a frame, and what is the direction of that action?

- Do you need any camera movement to add motion to this shot? In other words, does the camera follow the actor or vehicles in the shot, and in what direction?

- Do you need any special lighting? The lighting depends on what type of mood you're trying to convey (for example, you may need candlelight, moonlight, a dark alley, or a bright sunny day).

- Do you need any special effects? Illustrating special effects is important to deciding whether you have to hire a special-effects person. Special effects can include gunfire, explosions, and computer-generated effects.

After you determine what makes up each shot, decide whether you want to storyboard every shot or just the ones that require special planning, like action or special effects. If you want to keep a certain style throughout the film — like low angles, special lenses, or a certain lighting style (for example, shadows) — then you may want to storyboard every shot. If you only want to storyboard certain scenes that may require special planning, keep a shot list of all the events or scenes that jump out at you so that you can translate them into separate storyboard panels.

**Even if you've already created your shot list, you aren't locked into it. Inspiration for a new shot often hits while you're on set and your creative juices are flowing. If you have time and money, and the schedule and budget allow, try out that inspiration!

Storyboard panels

A storyboard panel is basically just a box containing the illustration of the shot you envision for your film. It gives shot by shot visual cues for the film and is helpful for your production team. Use the description panel underneath the storyboard boxes to write down important information that describes in detail what the illustration doesn't show or enhances what is drawn in the frame above. For example, include any important dialogue, camera directions, scene numbers, or special-effects instructions.